Gadija Davids writes

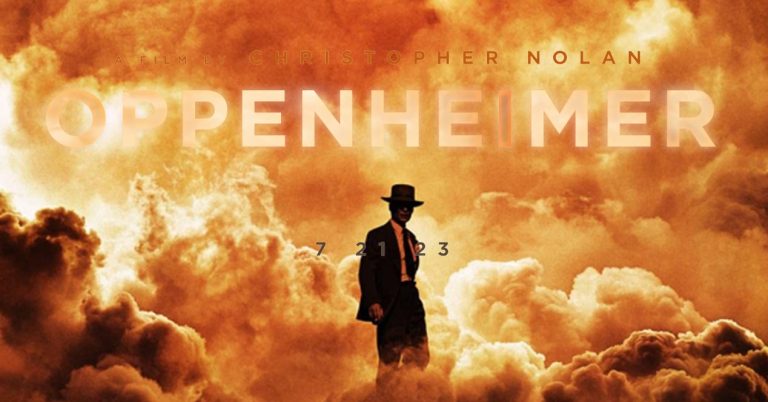

Oppenheimer depicts the convergence of scientific innovation, the battle for political and military power, and the personal greed for notoriety. Much has been written about the historical accuracy, the skewed narrative, and the skill of the film’s lead, Cillian Murphy. However, for the sheer brilliance of a story well told through film, there is little to fault Christopher Nolan’s work. This piece will discuss the film for its cinematic value, which, despite Hollywood’s power to influence, is all that movies should be assessed on.

While the film shows key figures in history, from J. Robert Oppenheimer, who spearheaded the development of the world’s first atomic bomb, to US President Harry Truman, who ultimately gave the go-ahead to murder thousands in the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Nolan also delivers a narrative about ambition, the search for knowledge, and the misunderstandings and events that eventually lead to catastrophic consequences.

The film opens on a young Oppenheimer who eventually delves into the world of theoretical physics. It’s made up of figures who discuss probabilities, and his main focus is how stars collapse and form black holes. This was all new in the early 1900s, and with the knowledge we now have, it is easy to see the parallels between the death of a star and how the A-bomb consumes everything around it.

One of Oppenheimer’s key observations, and fears, is that the nuclear bomb would cause the end of the world – that was how little they knew of its effects. The film portrays scientists who are all enthralled by the possibilities and power of these new discoveries, which followed Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, and the later innovation, which essentially split the atom (this was initially thought to be impossible).

The splitting of the atom ignited scientists’ minds of the possibilities of what this could mean for their understanding of the world. But as this discovery was made when the world was at war, everyone’s minds, including the scientists, were focused on what it would take to end the years of battles. And this is where Oppenheimer gets drawn in by the US military to begin work on a bomb to end World War II.

Conflicts arise amongst his team on whether to take the atomic or hydrogen route. The H-bomb was expected to be more devastating than the atomic bomb, and in the film, Oppenheimer is quick to direct war-hungry politicians and advisors away from exploring this more dangerous option.

While the US and Russia are allied at this point, there is still a distrust that extends to sharing military knowledge. This increases the urgency to develop the weapon and escalates the levels of state paranoia and distrust. These all prove key influences in the development and eventual use of the A-bomb.

While Oppenheimer finds himself plagued by the weight of a nuclear death device, and the likelihood of spies infiltrating his group of scientists, he faces an unknown threat in Admiral Lewis Strauss (played by Robert Downey Jr). The latter is revealed to have worked to discredit Oppenheimer within the scientific community, even devising ways to hype-up his links to communist organisations.

The close-up angles, use of black and white, and colour all draw the viewer into the mental challenges Oppenheimer faced during this pivotal point in history. But what cemented my appreciation for this cinematic work was the use of sound to accompany the intensity of key scenes. The scene showing the testing of the A-bomb in Los Alamos, New Mexico, depicts this perfectly. Instead of a loud explosion when the bomb is detonated, we hear Oppenheimer’s laboured breathing. It at once drives home the physical and ethical impact of this deadly device and comes across through the fear and fascination playing across Oppenheimer’s face.

It’s through this cinematic device that Nolan achieves the goal of showing the dynamic situation that the world was in, and the impact that key powers would have in setting the world on course for the Cold War, and the later shift to a multi-power world order.

Oppenheimer was still hailed for his role in the development of the atomic bomb, despite its obvious genocidal and long-lasting effects on the people of Japan. The film also depicts him as a vocal advocate for stronger regulations on the use of nuclear bombs, which raises the ire of the military and certain figures within the US political sphere. There was clearly financial and political capital to be made from this weapon, and many wanted a piece of the atomic pie.

A campaign is then launched by Strauss to instigate a show-inquiry (which gets no media coverage) to discredit Oppenheimer in the scientific community and drown out his attempts to use the lessons from the US’s mass murders in Hiroshima and Nagasaki towards innovations that would be in the public interest.

The dominant view may be to steer clear of anything nuclear, but we cannot ignore the impact it has had on medical diagnosis, energy, and even agriculture. And in an ideal world, these avenues should have been the first to be explored before the development of “a bomb to end all wars” was even considered.

At the end of the film, it is left to the audience to determine whether Oppenheimer was just a pawn in a greater scheme for power, or if he was a key player in the destruction of millions of lives. Was he dancing between the raindrops morally, or does he have a greater case to answer to humanity?